Customer Testing - Selling The Empty Box

When creating a prototype, there are two things we need to test; the item and the box.

The item is the product or service that you’re creating; you want to be confident that you can consistently deliver on your promises.

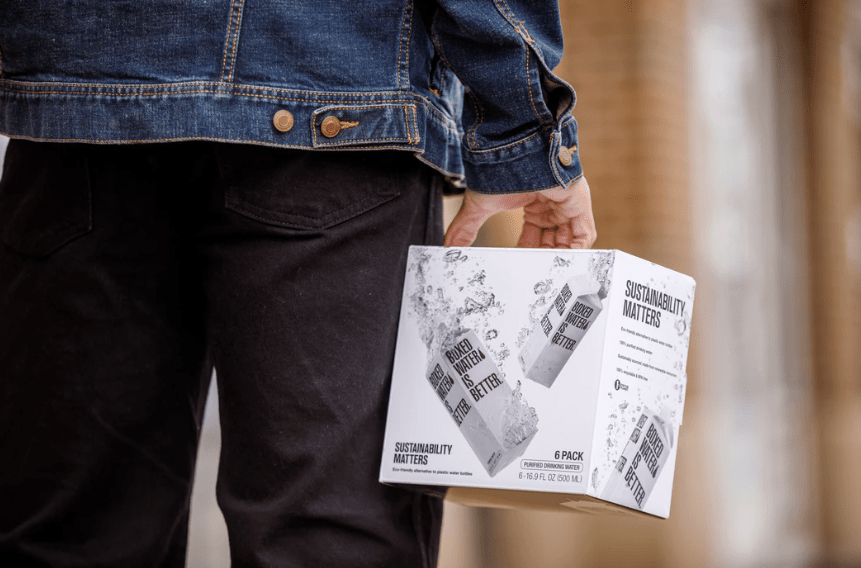

The box is the packaging and advertising that surround the item; the images and words that catch the customer’s eye, and customers scrutinise the box to entertain the idea of a purchase.

These do not have to be tested together.

You can test the box separately from the item, in fact it’s often better to do it first.

A strong business requires both a great product/service and an enticing Value Proposition, so eventually you need to be confident in what you sell and how you frame it.

The difference is the sequencing of tests.

You can test a Value Proposition in a weekend, but designing a new product/service might take months or years.

I’d argue it’s better to have a proven Value Proposition then work out how you’ll deliver on it, rather than to have a functional product that doesn’t interest your customers.

More importantly, if there’s a disconnect between what I make and what customers want, I need to know that right now.

The longer I wait to find out, the greater the sunk cost and the harder it is to pivot.

The job of an entrepreneur is to sell something people want, even if it’s different from what people have bought before.

The natural instinct of an inventor is to obsess over their product, rather than their customer.

That’s why this testing method might feel uncomfortable for technicians.

You should consider taking an empty (branded) box with you to your next interviews and tests, to see how customers interact and assess its promises.

It doesn’t have to actually be empty, you could put some in some Styrofoam of a small weight to give the illusion of content, the point is to see how the customer absorbs and reacts to your messaging.

This is similar to what web and app developers do with wireframes, creating static images and pretending that they’re functional to see how people engage with the concept.

What to put on the box

The purpose of the box is to highlight the Value Proposition of what you sell.

This refers to the underlying benefits, like relieving a pain point or giving people something they aspire to.

It could be a cologne box with the image of Roger Federer holding a trophy.

It could be a headphone box that shows a person tuning out the noise of an airport.

It could be a box for recyclable coffee cups, declaring that the days of landfill are over.

It could be a voucher for a day spa, listing the benefits you’ll receive during your stay.

It could be a referral to a psychologist, highlighting the types of customer they generally assist and the benefits they have received.

It could be a box for a new type of remote camera, that can reach inaccessible places and send back the images.

It could be a box for an online library of video tutorials – this doesn’t actually need a box but people like having something to interact with.

Your job is to design the best expression of your Value Proposition.

This might be before/after shots, statistics of improved performance, customer testimonials, pictures of someone happily using the item, or words describing how their life will change for the better.

Does it have to literally be a box?

No, but it does need to look like a legitimate version of whichever medium you choose.

If it’s a website, make it a nice one.

If it’s a brochure for a service, print it in colour and make the layout look professional.

If it’s a box, use high res photos, clear fonts and sturdy cardboard.

You won’t get genuine insights if your customers feel like they’re holding a kindergarten project.

The point of the empty box is that it’s a test you run before you’ve got all of the finer details sorted out.

What to measure in your tests

The first test is the customer’s first impression – do they register that this might be of interest to them?

I once did market research for a chocolate company, where I had to walk down two pretend supermarket aisles full of chocolate.

After I walked past the first aisle, I had to tell them which brands I remembered seeing (Toblerone, Lindt, Ferrero Rocher, Milka, etc).

The second aisle was set up almost identically, with a new addition – boxes of Cadbury CoCo – and then they asked me the same question.

The aim here was to see what caught my eye, did the new addition register as a point of interest?

I cannot stress this enough – there was no chocolate tasting involved.

It might have been the best chocolate in the world, but if it was invisible in stores then it wouldn’t matter.

And since supermarkets don’t let you sample the chocolates until you’ve paid for them, this was a purchase based on the box and not on taste.

The second test is understanding how customers prioritise different aspects of the item.

Did their eye jump to the price tag, or to the list of components/ingredients?

What questions do they ask?

Are they interested in warranties, statistics or examples of others who are using it?

What seems like the dealbreaker to them progressing with a purchase?

The third test is in asking for a commitment of some sort – this separates politeness from genuine interest.

People will say nice things to you out of courtesy, but when pushed for an order will suddenly become a little more honest.

Just to be clear, you don’t need to accepts their money or sign a contract on the spot, you want to know if they are willing to progress.

E.g. you create a landing page for an event, with photos and a lineup.

When customers click on the button to buy tickets, you can send them to a page that apologises for tickets being temporarily unavailable and collects an email address to notify them when they are available again.

Their willingness to click on “Buy Now” is the most genuine form of feedback.

Two Types of Meetings

Not all meetings with customers are the same – I’d broadly describe the two types as being interviews and sales pitches.

Interviews (also known as Customer Empathy Interviews) are the chance to ask questions without any hint of sales, allowing your interviewee speak freely.

The aim here is to understand how your customer thinks, what needs and constraints they have, and how they evaluate different options.

We want to ask lots of open-ended questions and record how people approached each topic.

What didn’t they say?

How did they seem to feel?

Sales pitches involve questions, but they build towards an offer, when you ask them if they’d like to buy.

These teach you a lot, especially when it comes to “If…then…” questions.

If we can accommodate 20 guests, will you sign up today?

If we can do it for under $120 per head, can we sign the contract right now?

If we can build you a version with these custom features, will you put the deposit down today?

This gives you real honesty – the customer has to reveal their true dealbreaker or agree to the purchase.

My suggestion is to start with interviews to form an initial understanding, then use pitches to confirm your suspicions.

Also, nobody likes to feel blindsided – if you ask for their “help”, don’t turn your meeting into a high pressure sales conversation.

You win or you learn

The outcomes here are all pretty good.

As a reward for your bravery in this process, you either confirm that customers like the item’s description/Value Proposition, or you gain invaluable insight into where there’s a disconnect.

Either way, you’ll feel better for having run the test.

I’ve found this useful for testing the design of our programs.

By starting with an official looking brochure, I can talk to each prospective customer about the benefits, features and prices of a new program to gauge their reaction.

Did they linger on the price, or on the amount of coaching they receive?

Were their questions on the topics covered, or who would be teaching them?

Were they interested in who else was in the cohort, or how soon it started?

At this stage we hadn’t worked out who was teaching which session, which topics to include, or where it would be held – we first wanted to know what was most important to our customer.

Once we had 10-15 of these interviews, we then went back and designed a program and budget that best served our cohort, then asked each customer if they’d like to sign up.

In case it’s of interest, I learned that the biggest issue for startups is price, the biggest issue for more established businesses is the track record of the facilitator, and the biggest issue for a not-for-profit/institution is the credibility of our brand.

This changed how we design and sell the same underlying service to each participant, modifying the message to match their dealbreakers.

We now run a cheaper, shorter program for startups tailored to the cohort’s areas of interest.

We also spend more time talking about our qualifications and outcomes to larger clients, and no longer feel the need to apologise for our prices.

This stops us barking up the wrong tree, and increases the number of customers who end up saying “Yes”.

Selling an empty box might feel like a distraction at first, but it has the potential to save you a lot of stress and heartbreak.

If customers don’t “get it” when they see the box, then you’ve either got the wrong customer, value proposition, sales channel or wrong product lineup.

If you can use some cardboard and a few meetings to work that out, it’ll be the best money you’ve spent.