Lessons From The YGAP First Gens Accelerator

This week I have been at the YGAP First Gens Accelerator, a five-day intensive with twelve fantastic social entrepreneurs.

Each brings a passion for change, be it the way in which refugees find good jobs, get into professional networks or access appropriate medical care, how STEM fields can be made more compelling to girls at school, or how we can better use technology to train disability support workers.

Here are some of the insights that proved to be valuable for the participants, as well as myself.

Everyone needs help. Everyone.

No entrepreneur can truly walk the journey alone, so a willingness to ask for help becomes a source of strength.

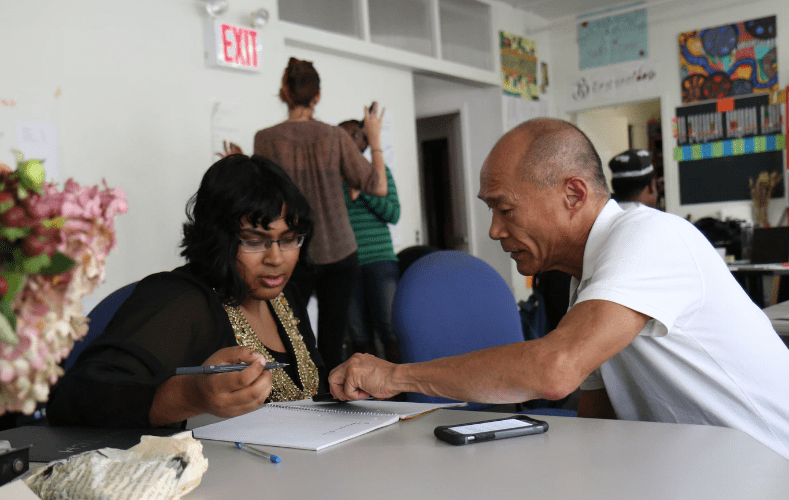

This might be a 1-1 session with a mentor, a mastermind group of three, or having a room full of clever entrepreneurs giving you honest feedback.

This is particularly relevant for pitching – after you’ve given a presentation, having the room ask you direct questions about what you actually do.

It’s highly likely that people will congratulate you for being a good person who does good things, but if people still don’t understand what you sell or how you make money, then your presentation needs to change.

This can only happen in a culture of support and vulnerability, and when done right it can be transformational.

Being accurate isn’t the same as being clear.

A lot of social entrepreneurs don’t see themselves as fitting into a simple, predefined category (e.g. being a dentist or being an after school program).

Therefore, their solution is to create a new category using long words (e.g. we’re a data-informed peer to peer recommendation engine that enables new networks).

This might be an accurate description, but certainly isn’t clear.

Any two of those words could be simple, but having heard you talk about your business I couldn’t give a 20 second summary to someone who wasn’t in the room.

Perhaps it’s better to put yourself in a slightly inaccurate category in the first 10 seconds of a talk, knowing that you have the next few minutes to properly explain your work.

The accurate description might be true, but if it makes your audience switch off, what’s the point?

Your structure does not define your impact.

Being a not-for-profit does not make you a saint, in the same way that being a for-profit does not make you the devil.

There are also two kinds of not-for-profits; businesses and charities.

Making the switch from being a charity to being a business is huge – it means finding customers instead of grantors, asking for a sale instead of a donation, and basing your strength on your desirability to a customer instead of your operational efficiency.

Instead, your impact comes from your Theory of Change, the simple process of how you consistently make positive improvements in the world.

A Theory of Change should be expressible on five post-it notes:

The problem we’re trying to change is…

It is an important problem today because …

The root cause is…

To address that we will…

And measure…

None of those are based on your legal structure, they’re all based on a correct diagnosis of the underlying problem, and the implementation of a clever solution.

Eight-word mission statements are brilliant.

The best mission statements should be simple; up to eight words that describe a target population or area, a verb, and a measurable outcome.

e.g. Boosting incomes for smallholder farmers in India

Connecting skilled migrants with appropriate jobs

Providing meaningful employment for women in Kenya

Using long sentences or cramming your solution into your mission is cheating.

The mission is the part of your idea that won’t change; you might change how you help a particular group, but you won’t stop trying to help them.

Good ideas survive competition.

A great activity is to go back to the exploratory stage of your idea, and create a list of 50 ideas that could achieve your mission.

50 is a lot, and that’s important – it’s the last 10 ideas that often produce the most radical innovations.

The aim is to go through a few rounds of ideation, sometimes on your own, sometimes with friends, sometimes using innovation prompts (e.g. combining two existing ideas, 10x thinking, etc).

You can then narrow down the 50 to a top 5, and then a top 2.

This creates a competitor to your initial idea, and good ideas survive competition.

You do not lose anything by taking the best ideas, or combining elements of several ideas into a single larger project.

Complex ideas do not suffer from simple explanations.

I am happy to admit when I don’t understand something, which happens quite a lot.

Many of the concepts floated during the week had enormously complex descriptions, or were simplified without being simple.

e.g. There is not enough ethnic and cultural diversity in the legal profession.

This is a simple sentence and it sounds true, but if I’m honest I can’t tell you why it’s true or why the problem exists.

If I don’t know those things, it will be hard for me to commit to taking action and supporting the cause in a meaningful way.

Sometimes there needs to be a second half to the sentence, perhaps led by “due to…” or “and that means…”.

Tools like storyboards and diagrams can be helpful, as they give the audience more clues as to who is involved, what actions are taken, and how change is made.

If you can’t give a simple explanation, maybe you don’t understand the topic well enough.

Your idea is not so complex that it couldn’t be processed by a 10 year old.

Measuring success is not the same as measuring activity.

There’s a temptation to measure the actions of your business instead of the net impact.

For example, you might distribute an educational program to X people, or sell X widgets.

What do those programs or widgets actually do for people?

If you deliver career advice sessions and your participants still can’t get jobs, how impactful have you been?

This question can also be framed as “How will you know that this is working?”

These improved outcomes need to be attributable to you, or else you can’t really claim them.

Financial modelling is not the same as using Excel.

There are two components to creating a strong financial model, and they must be done in this sequence:

1. Deciding on how you create revenue and spend money.

2. Entering these concepts into a spreadsheet to see a net result.

If you do the Excel work first, you end up with a colourful sheet with big numbers that are completely meaningless.

For many social entrepreneurs, the most important conversation is “Have we picked the right revenue and cost model?”.

In other words, are we charging the right person? Are we hiring the right staff? Are we using the right pricing structure?

Once you’re happy that you have the right model, the spreadsheet becomes relatively simple.

Without the right model, the spreadsheet is false hope.

Your name and logo are really important.

I am not an expert on business names and logos, but I know enough to spot trouble.

A good name and logo should give your audience a rough understanding of your industry and your idea – even if it’s just a clue (like how Who Gives A Crap and Facebook suggest what they do).

An ok name and logo can be general and bland, if you then breathe life into the brand (like how Apple, Amazon, Uber and Aesop don’t mean much on their own).

A bad name and logo distract from the idea, either by suggesting the wrong industry, being hard to spell or are visually overwhelming.

If your audience leave the pitch remembering your name and not the brand name, something isn’t working.

Someone should grill you over your first three slides.

We had a brutal session when one of the mentors made each team present their name, description, problem and solution.

Each line was scrutinised and clarified, with each team needing several attempts to get it right.

At first the entrepreneurs were upset, but in seeing the same treatment applied to all of the others, slowly realised how great the advice was.

This unpicks the jargon, the fluff and the unnecessarily long descriptions.

Once you have a strong core, you can add elements like personal stories, photos and prototypes.

Without a strong core, your audience won’t understand what you actually do, and are likely to lose interest.

Showing is better than telling.

A good photo can drastically cut down the time to the “Oh I get it!” moment.

It convey emotions that are tough to describe, and give you credibility that would sound arrogant if you said it yourself.

If you run a robotics and coding class for young girls, having a photo of a young girl entranced by the robot she’s building says everything.

If I can see the work in action, I’ll take everything else you say more seriously.

If I can’t picture the work in action, it’s hard for me to be excited about the idea.

Finally, there are the sections that I taught.

A lot of these are captured here on this site, such as:

The Three Lenses of Innovation

How To Fill In A Business Model Canvas

Free eBook – Building A Strong Business Model

What Is A Financial Model?

Revenue Calculations And Forecasts

Variable Cost Calculations

Fixed Cost Calculations

Profit Calculations And Analysis

Assumptions Tables And Excel

Direct/Indirect Substitutes

Cash Cows, Small Margins and Loss Leaders

The Pitching Checklist

Wisdom From The Pitching Panel

The Essence Of Strategy

How To Fill In A Value Proposition Canvas

Testing Your Assumptions

Sophisticated/Unsophisticated Customers

These twelve entrepreneurs will be pitching for up to $25,000 each in three months’ time, and I can’t wait to see how their ideas evolve.