Creativity and Risk

When writing the earlier post on Season Two, I started thinking about my favourite movie and TV show, and what they have in common.

What struck me was a common thread – the amount of calculated risk taken by the creators, that led to something extraordinary.

But not risks that were taken right away.

The parts that became iconic weren’t deliberately engineered from the beginning – they grew and evolved once the idea was up and running.

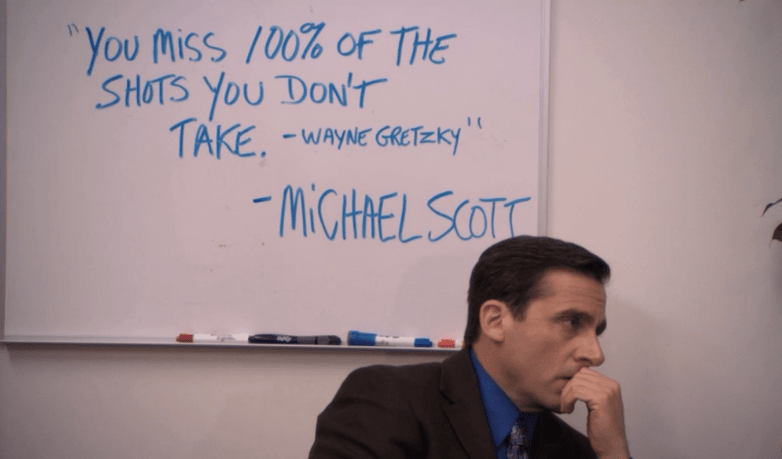

Steve Carrell

My personal favourite comedic performance is that of Steve Carrell as Michael Scott in the US version of The Office.

It's important to remember the context: all signs pointed to the show being a huge disaster:

- US remakes almost never work

- Cringe humour hadn’t become popular in America

- The cast were almost entirely unknown

- There were only 12 episodes of the UK version to copy

What is remarkable is the way the producers turned those weaknesses into strengths.

The first season wasn’t very good – it felt like an imitation, as if they had a new cast reading the UK scripts.

What probably sounded good in planning meetings wasn’t translating onto the screen.

Low risk led to low reward.

Then the show hit a magical mark: they ran out of episodes to copy.

New, original ideas were written, designed specifically for their cast and their audience.

Steve Carrell was given license with his character, and turned the role into something far deeper than his UK counterpart.

Part way through the second year, you can feel the show change.

It took a while for audiences to regain their trust in the show, but once they did it became enormously popular.

What I find so inspirational is that all early signs would have suggested that Steve Carrell should have passed on the show, and that it would bomb.

But Steve saw something different – an opportunity to make the role his own, if only it could survive the first year.

The limited UK seasons were actually a blessing – giving the cast enough material to get started, but forcing them to create their own concepts and quirks.

The approach often fails, and we’ll probably see many more failed adaptions in the coming years. Each will try to play it safe, and it won’t make much of a cultural impact.

Steve’s approach to risk also backfires, and Dinner for Schmucks and Evan Almighty won’t go down in history.

I guess he’ll have to console himself with the enormous success of The Office, Despicable Me, The Big Short and Foxcatcher, plus a Golden Globe and an Oscar nomination.

Heath Ledger

Batman has been around in comics since 1930, a heritage that makes the character a cultural icon.

On screen, Batman has never been taken particularly seriously.

Adam West famously played the role in the 1966 movie and TV series, which was then revived by Tim Burton in 1989, and some woeful efforts from Joel Schumacher in the mid 90’s.

The idea that Batman could win an Oscar is laughable.

Or at least it used to be.

In 2005, Christopher Nolan attempted something borderline impossible; making a serious Batman movie set in the real world.

No supernatural villains, no corny one liners, no nipples on the batsuit.

The result was Batman Begins, a film so successful it launched an entire genre – the gritty reboot.

The film’s villain wasn’t particularly well known, a role that hadn’t been featured on screen before.

For Christopher Nolan, this had to have been a deliberate decision.

The first movie was about establishing a new cinematic world where Batman was plausible, and the focus had to be on establishing the main character, not a villain.

The film ended with a teaser, a calling card from a criminal known as the Joker.

It was a nice twist at the end, foreshadowing the return of a well-known nemesis, and everyone was happy.

That is, everyone was happy until the casting news came out.

We were then told that the role had gone to this guy:

The response was vitriolic – and unanimous.

This picture that reminds me about the dangers of crowd forecasting:

Image -GeekTyrant

The world agreed, Nolan had got it wrong.

Heath Ledger couldn’t do it, and this was going to be a disaster.

The world forgot a crucial detail – Nolan hadn’t been looking for the old Joker.

He had created a new universe for Batman, and since he had some time to experiment with it, had managed to design a new Joker that specifically worked for him.

To do that, the requirement wasn’t “Who looks like The Joker” but instead “Who is the most creative actor who can take a risk something original”

When you look at it like that, the choice makes more sense.

Ricky Gervais has a great quote:

“I’m jealous of people who haven’t seen The Godfather, because they get to watch The Godfather for the first time”

That’s how I feel about The Dark Knight.

Heath Ledger didn’t become Jack Nicholson, or Cesar Romero.

He developed a different kind of crazy; famously created by locking himself in a motel room alone for six weeks.

The results are stunning.

You can’t take your eyes off him, a completely transfixing performance.

It turns out that inspiration struck from an eclectic range of sources – for example the haunting voice coming from an obscure old Tom Waits interview from 1979

What I find so impressive is the creative risk taken by both the actor and director.

Firstly, that they were willing to risk the character completely flopping and looking ridiculous.

Secondly, they waited until they had established the series before experimenting with the famous villains, learning from audience reactions and their own reflections.

Thirdly, the dedication and energy that they each brought to the project.

It would have been so easy give a safer performance based on traditional elements of the character, but that would have led to a result like Mickey Rourke in Iron Man 2 – decent but forgettable.

Tragically, Heath never got to see the end result of his work.

I can only imagine it being like the Van Gogh scene from Doctor Who – an artist who dies before receiving their highest praises.

In 2009, Heath Ledger posthumously won the Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor.

The Dark Knight is #4 on IMDB’s Top 250 movies of all time.