BMC Part Nine: Cost Structure

(If you’re using the Canvas, you’ll love my free Business Modelling eBook, full of tips for inventing and testing ideas that will change the world)

So far, we’ve made a lot of big claims on the canvas – all the Resources we’re going to purchase, people we’ll employ, Activities we’re going to perform, Channels we’ll operate, Relationships we’ll manage…

These things aren’t cheap.

We need to get a sense of our financials, to see if we actually make money from each sale, and quantify how many sales are required to break even.

That’s why it’s so important to understand our cost structure – it tells us the total amount we’re due to spend, but also the format in which we spend it.

For example, we need to know which costs are one-offs, and which are ongoing.

We also need to understand which costs are fixed, and which costs are variable.

One-Off Costs

Startup costs are an initial hurdle; items and services that are necessary to begin trading, but then last for many years.

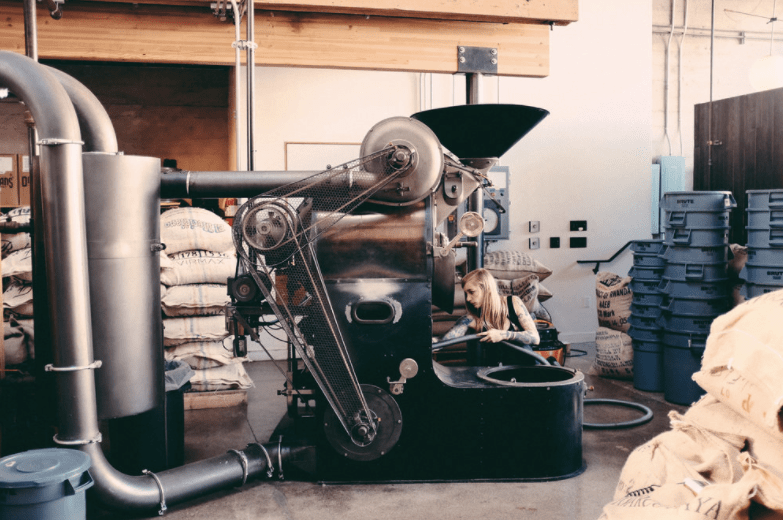

This includes fitting out your shop or office, building your website/platform, designing your brand identity, and buying any machinery required to deliver your Value Proposition.

On paper, there are long term advantages to buying things upfront.

Per unit, it’s generally cheaper to own things yourself.

The catch is, this advice only works if you know you'll be around for many years.

For a startup, you’re better off renting/borrowing/bluffing your way through, as this shrinks the risk and cost of trialling a new venture.

Ongoing Costs

Most costs are a continuous financial drain – such as raw materials, staff time, annual licences, rent, utilities, and maintenance of your equipment.

It’s important that we know our average monthly figure – the amount of cash we need to spend in a typical month.

e.g. We spend $40,000 in month 1, then only $8,000 per month for the rest of the year

Fixed Costs

These are the purchases that cost a flat rate, no matter how much (or how little) you use them.

Rent is a great example, you pay your landlord the same amount irrespective of how many customers come through the door.

Same for lighting, heating and internet.

These are generally items or licenses that are binary – you have them or you don’t.

They’re also things that aren’t directly consumed by your customer, and aren’t “used up” in the process of making a sale.

e.g. Our fixed costs are $3,000 per month, even before we make any sales.

Variable Costs

These are the items that are directly used in serving a customer, and which vary based on your total number of sales.

For example, if you double your sales, you’ll use twice the number of shopping bags, paper cups, shipping costs, raw ingredients, etc.

It also may mean that you need to perform maintenance on your equipment more frequently, or need to roster more staff on busy days.

Some costs are semi-fixed.

This means they are fixed up until a certain point, but then you have to pay more.

For a café, a single coffee machine might be able to produce of a maximum 100 coffees per hour. As soon as you want 101 coffees per hour, you need a second machine, and a second barista.

That means the café makes a good profit when doing between 50-100 per hour, but not as much profit when doing 105 per hour.

When it gets up to 130, profits start looking strong again.

For other businesses, these tipping points might be things like the amount of traffic your site can handle, or the capacity of your warehouse.

These costs are flat, until you need to upgrade to something much bigger.

Maybe it’s the number of staff you need each day, or the need for a second shopfront.

e.g. Each pair of shoes we sell costs us $25 in materials, manufacturing and shipping.

Two Principles

There are two rough principles worth noting here:

1. Fixed costs are generally more economical than variable costs.

2. Variable costs reduce your breakeven point.

Which one does your idea need?

If you’re a large company, moving to own your own methods of production can save serious cash. It can also be a huge distraction, or assets you don’t want on your balance sheet.

If you’re a small company, moving production to a partner creates variable costs, which is a much safer way of operating.

It also makes you reliant on that partner, which can get tricky.

Quantifying Invisible Costs

It’s easy to let invisible costs sneak up on us; things like the cost of acquiring a new customer, or the cost of retaining an existing customer.

By tracking the total amount spent on acquisition, then dividing by the number of customers, we can find the average amount spent to bring on each new client.

The same goes for retention.

By understanding how much these things cost, we may discover that some customer segments just aren’t worth chasing.

It’s possible that we’re losing money with each customer we acquire.

Four questions for your business

· Where does our money get spent?

· Which costs are one-off and which are ongoing?

· Which are fixed and which are variable?

· Could we change our cost structure to improve our chances of success?

Now we head to the last box on the canvas: Revenue Streams...

This is a multi-part series on the Business Model Canvas.

If you’d like to jump straight to a particular section, go to:

Overview: How To Use The Business Model Canvas

Desirability: Customer Segments, Value Proposition, Customer Relationships, Channels

Feasibility: Key Resources, Key Activities, Key Partners

Viability: Cost Structure, Revenue Streams

Then once you've made your first canvas:

Reviewing: After Your First Model, Alarm Bells

Reinventing: Testing, What If?

Improving: Metrics, The Business Model Environment

Extensions: Pitching, Social Impact, Making It Great, What Next?