In Defence of Outrageous Salaries

Casino Royale, Sony Pictures

Today’s headlines are about Daniel Craig, and how he’s been offed $200m to do two more Bond films.

There’s a moral outrage that appears whenever anyone earns a ridiculous amount of money like this.

“How can a person possibly be worth that much money?”

“How can they earn 100x more than their staff?”

I used to feel the same way.

My mind was changed at ANZ.

When I was there, the CEO earned $10.1 million dollars a year.

By contrast, I was on $45,000.

Which meant the CEO earned what I did in a year, in a little over a day.

It would be easy to find this demoralising.

But then I heard about the last CEO, the impact of the GFC, and the old problems with the business.

Then I heard about the company’s new strategy, and how well it was working.

All driven by the change at the top.

It made me think: If I was a shareholder of a mediocre company, and had the chance to bring on a brilliant CEO who could turn things around, what would I be willing to pay them?

If the CEO of ANZ is directly responsible for company profits increasing by several billion dollars, how much should they get paid?

Better yet, if ANZ didn't have a visionary leader, how much would they be willing to pay to lure one across?

That's how you end up with enormous salaries.

The same goes for Alan Joyce of Qantas, who now earns around $13m a year.

He also turned around one of the country’s most important businesses, going from billion dollar losses to billion dollar profits.

Pay him whatever he wants.

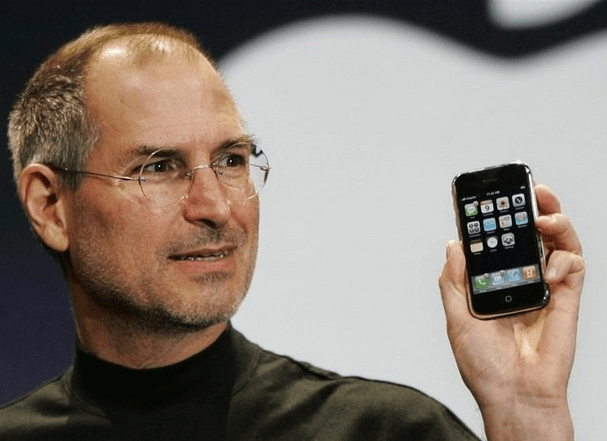

Another way of thinking about it; how much do you think Apple would pay for a way to clone Steve Jobs?

The trouble comes when the pay doesn’t match the results.

When a CEO earns millions while the company stalls, or deliberately underpays staff, they should be called to account for the injustice.

When an expensive free agent doesn’t perform for a sports team, they attract boos and critics – and rightly so.

But if that free agent delivers a championship?

Pay them whatever they want.

Daniel Craig’s Bond films have been recently earning over a billion dollars each, in no small part due to the man himself.

Getting it wrong would be a very expensive mistake.

If there were a dozen equally capable Bonds, this wouldn’t be happening.

If there were a handful of Steve Jobs equivalents….

If there were a constant supply of CEOs capable of billion-dollar turnarounds…

But there isn’t, and so when that rare person emerges, they get paid handsomely.

The part that make me feel sick is when people earn huge sums without the talent, but because of their manipulation of the law, nepotistic connections or their exploitation of the poor.

But if a single person can bring about a tremendous, positive change?

I get it.

Money isn’t fair.

That unfairness is what drives the work of Business For Development, as well as most of the Social Enterprise community.

When we are designing business projects, we look at the ROI – Return on Investment.

If we put a million dollars into a project, how much benefit can we create?

A nice idea, with no ROI, probably won’t get funded.

A boring idea, with a great ROI, is easy to get off the ground.

That’s the lens through which I look at salaries.

The question for me isn’t “How do we make large salaries illegal?”, it’s “How do I learn to become THAT useful?” and "Who can revolutionise our organisation?"

Charity CEOs are criticised if they get paid well, but surely the real question should be: What’s the return on that investment?

If a talented leader can be a visionary, if she can be the Elon Musk of our industry and massively escalate the amount of funds raised/impact created, surely we should pay her whatever she wants.

For those looking for a great way to spend 18 minutes, I highly recommend Dan Palotta’s TED talk on the subject: