Value Propositions: Being The Cheapest

(If you’re crafting Value Propositions, you’ll love my free Value Propositions eBook, full of tips for designing and testing compelling Value Propositions that will delight your customers.)

We’ve previously looked at being better vs being cheaper, and seen that in general, it’s easier to compete on quality than on price.

But if you get it right, being perceived as cheap can make you enormously successful.

Customers will look for ways to save money, but not at their own detriment.

Don’t believe me?

Think about the difference between “Cheap and Cheerful” and “Cheap and Nasty”.

I’ll bet you’ve experienced both, and I’ll bet you can tell the difference.

That’s why low prices, on their own, are not a persuasive value proposition.

The successful brands are the ones who are the right kind of cheap.

Let’s look at some examples.

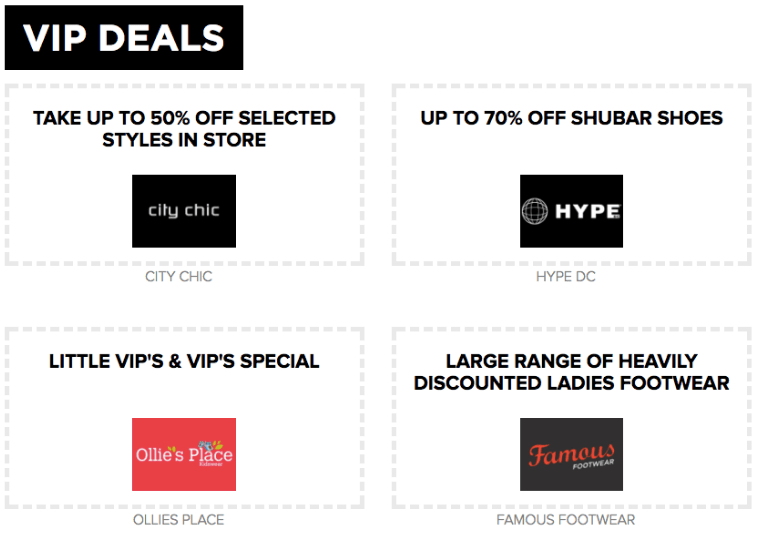

Image: Harbourtown Melbourne

Feeling like a secret

“Please accept my resignation, I wouldn’t want to be part of any club that would accept me as a member” – Groucho Marx.

Being an insider is a wonderful feeling – recognition that you are special and deserve secret information.

It’s a feeling that can be manufactured.

Companies will set up mailing lists, loyalty programs and exclusive benefits that reward their inner circle.

Think of companies like Myer who host VIP shopping nights, or Jetstar emailing special offers to their frequent customers.

Each purchase comes with bragging rights, we can tell our friends about our exclusive access to these deals, and therefore associate ourselves with being an important person.

Brands tell you that you received a discount because you’re worthy, and this eliminates the natural suspicion of low prices.

If everyone else had access to these same deals, they’d instantly lose their charm.

Image: Industy Super Funds

Disdain for the average

One tactic for creating permission to switch brands is to mock your more expensive competitors.

This is a fine balance, and it comes back to the principle of “Punching Up” vs “Punching Down”.

It’s generally OK to make fun of those who feel higher up in life, like your boss, the rich, politicians, or in this case, more expensive brands.

By contrast, making fun of the poor, junior staff, refugees and inexpensive brands seems to be in bad taste.

This is an advantage for cheaper brands, who can use humour to poke fun at pretentious rivals, and highlight their empty, pompous claims.

Industry Super Funds use visuals to invite direct comparison, showing two similar people and their respective superannuation balances.

The dialogue is then the Industry Super Funds member poking fun at their friend’s decision to stay paying higher fees, and therefore missing out on more money when they retire.

Image: Imgur

Discounts vs low prices

We perceive a disparity between a $50 product vs a $100 product that today is 50% off.

We respond to those two offers differently, because the price signals which one is the better offer.

Discounts feel like a treat, like we have access to something outside of our usual price range.

We award ourselves the mental points of owning a high-value product, as well as the points for hunting down a bargain.

If you ever go on a shopping spree and leave feeling like you made a saving, you’ll know this sensation.

Remember, it’s only a bargain if you were willing to pay full price in the first place.

It may well be that the company never intended to charge the sticker price, instead using the “original” price to display the item’s worth, then using the “discounted” price to entice a quick sale.

This move is so sneaky and so common that it’s becoming illegal, with some countries now insisting that brands prove that the item was genuinely on sale for the higher price in the past.

By contrast, other brands make a standing offer to beat their competitors.

Bunnings Warehouse claims that if you find a cheaper price elsewhere, they’ll beat it by 10%.

What portion of their customers do you think take the time to research each item in detail? Hardly any of them, but we all shop there with the comfort of knowing that “Bunnings are cheapest”, even if that’s not strictly true.

Explanations for low prices

To avoid triggering suspicion, brands will often use a clever line to explain how they can offer something of good quality for a low price.

You may have heard ads that start with:

“Due to a shipping error, we’ve got too many…”

or

“Our End of Financial Year Sale means you’ll save on…”

Maybe the company will describe their business model to highlight exactly where the discount comes from.

Dollar Shave Club created one of the best ads in recent history to do just that.

IKEA use flat packs and warehouse style stores, making customers feel like they’re working for their bargain.

The nice bonus is The IKEA Effect – we love our new furniture even more because we built it ourselves.

Low sticker price vs low total spend

Why do bars have Happy Hour?

Out of generosity?

No, it’s because they know that a low sticker price (cheap drinks for a certain time) will lead to a larger total spend (the amount of drinks you buy over the whole night).

Likewise, Aldi promote their comparative basket cost.

They add up how much you’ll spend buying staple items at Coles or Woolworths, then highlight how much cheaper that same set of items would have been at Aldi.

That’s because we don’t get excited about saving 30c on baked beans, but we do like the idea of saving 30% off our total shopping bill.

Amazon and Book Depository are the same company, yet one advertises low book prices, whereas the other advertises free international shipping.

It’s completely irrational, but most customers have an irrational preference one way or another (I am always drawn to free shipping for some reason).

Budget airlines are notorious for this.

We use comparison sites, sorted by lowest price first.

We see a cheap fare, and start our booking process feeling like a winner.

The base rate is cheap, but then come the taxes, baggage fees, seat allocation costs, food, in-flight entertainment, a request for a donation, then a payment fee.

It turns out, our cheap flight is now comparable in price to a full service airline!

You’ll see ads for phone/internet/cable tv companies run ads with a low sticker price in huge letters, like “Just $39 per month for the first six months”, then small writing at the bottom of the screen that reads “minimum costs $1,440 over 24 months”.

Which number will your customer care about most?

Our customer tends to use one “rule of thumb” metric to gauge value, and this varies between industries.

Does your customer look at the unit price, or the total amount spent?

If it’s the sticker price, then it might be worth creating a loss-leader item that grabs attention, then focusing on increasing the number of items each customer buys.

If it’s the total price, then it’s worth designing packages around a price point.

You can then find your competitor’s equivalent and highlight the price difference – it’s worth cherry-picking the flattering comparisons.

Image: AAMI

So That…

What’s the incentive to switch to a cheaper brand?

Since our customer will be accepting something slightly less convenient or potentially lower quality, what do they get in return?

Discounts and dollars saved are meaningless without a frame of reference.

What we need is a “So that…”, such as

So that I can go on holiday

So that I can buy more of (item or service)

So that I can buy an additional (item or service)

So that I can feel smug

Customers make these trade-offs based on which comparison has the strongest appeal.

By acknowledging the other side of the bargain, we can remind them of why the discount matters, and thereby win the sale.

For example, when travelling for work, have you ever asked your employer to book you a cheaper hotel?

Of course not, because making a saving means nothing to you.

Per Diems however, allow workers to benefit from their thrifty decisions.

If you choose McDonalds over a fancy restaurant, you get to keep the change, and will use that to fuel whatever is your current top priority.

AAMI Insurance currently have a campaign with three people who saved money on their premiums, and used the extra cash to buy personalised garden gnomes.

Ridiculous, but it makes a point; save money over here so you can be eccentric elsewhere.

Try it for yourself.

For your industry, which of these could you use to capture your customer’s attention?

For more of the Value Propositions Case Studies series;

Part One featuring Louis Vuitton, AFL, Uber and TOMS

Part Two featuring Nespresso, Heineken, and Shoes of Prey

Part Three featuring a variety of Men’s Watches and Chocolate brands

Part Four featuring the classic iPod ads, Whiskey, Hardware, Butter and Barossa Tourism

Being The Best explores how companies frame themselves as industry leaders

Being The Cheapest covers strategies for demonstrating value for money

Social Proof examines how brands make themselves look popular and trustworthy

Cologne looks at how intangible gains are conveyed through imagery and design

Bottled Water compares ten brands selling the same product in different ways

If you’re crafting Value Propositions, you’ll love my free Value Propositions eBook, full of tips for designing and testing compelling Value Propositions that will delight your customers.