My Five Biggest Consulting Regrets

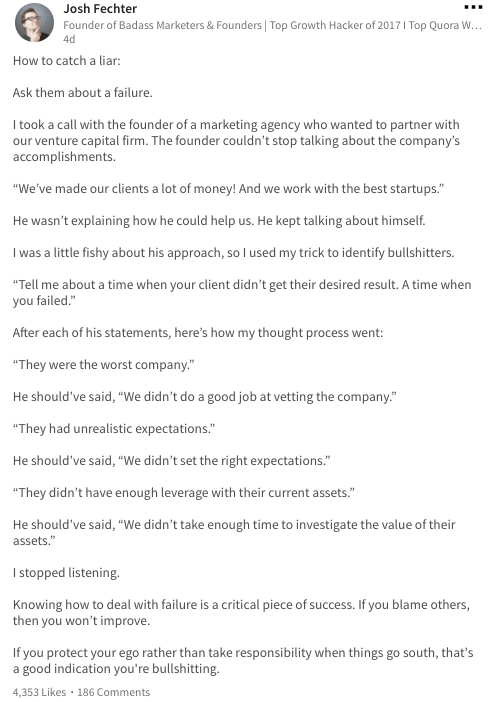

I saw a post on LinkedIn yesterday that said recommended asking prospective advisors about a time they’ve failed their client.

If they can’t, walk away.

They have no self-awareness or they’re lying to you.

Here's a screenshot:

Thanks to Josh Fechter for this gem

That idea sparked this article.

It’s not designed to make me look good, like when people claim their biggest weakness is “Working too hard” or “Caring too much”.

Here are five mistakes that have taught me a lot, and that I’m determined to never repeat.

Declining a beer after a session

A large part of a consultant’s job is gathering information.

This might be sales figures, customer feedback, progress reports, etc.

When starting a new project, you’ll send out a list of all the information you need in order to understand the situation.

Or so we tell ourselves.

Data is like the bones of a skeleton – rigid and complex, different shaped pieces fit together to form a working body.

The problem is, a skeleton can’t move without tendons and ligaments – the small bits of tissue that determine how two bones interact with each other.

In this case, ligaments are things like unspoken expectations, irrational biases, organisational scar tissue, vested interests and office politics.

All things that can’t be collated on a spreadsheet.

Instead, these are collected at the pub after work.

You need a high trust environment, a vulnerable relationship, and a genuine interest in the client you’re working with.

I got this wrong – since I formerly didn’t drink, I saw no merit in going out for a beer after a session.

I’d inadvertently dismissed opportunities that would have revealed some very interesting insights, as well as building closer friendships.

I could have sensed hesitation earlier, read the signs of a management change, understood why decision makers had an aversion to some options, or helped people feel more comfortable in expressing their doubts.

A concern that isn’t voiced in a session will continue to sit below the surface, and emerge at a later date, usually at a much more crucial stage of the project.

This became clear when I saw my colleagues use the pub chat to great effect – they’d find out the real story, and suddenly everyone’s behaviour made a lot more sense.

Making general suggestions without setting measurable goals

When assisting social entrepreneurs with their growth, it’s easy to fall into the trap of “cooking to the recipe”

This was something that my colleague and I disagreed on: they argued that an efficient consultancy followed a formula, one that could be picked up off the shelf by any member of the consulting team and implemented step-by-step.

Yes, this is a great way for a consultancy to make money.

It also allowed me to become complacent.

We could deliver a session and technically do a brilliant job of explaining our content.

However, if our clients came back a few weeks later and hadn’t implemented any changes to their business, how can we expect that their situation will improve?

I regret the times where, in my disinterest, I washed my hands of our customer’s challenges.

My job isn’t to follow a recipe, it’s to help people.

That means if they are struggling to see how to implement our suggestions, I need to help them create a measurable implementation plan.

It’s not good enough for me to say “Go and find ten customers”, unless I can articulate how I would do it in their shoes.

If I can’t articulate how I’d find ten customers, I should not be advising them.

Letting my dislike of the entrepreneur interfere with my work

Some clients have been really unlikeable.

It generally comes down to different flavours of rudeness; like being dismissive, sexist or arrogant.

When I was a very junior consultant, I’d have some entrepreneurs try and call me out in front of the group, or openly dismiss me.

My solution was to engage with them as little as possible, giving them the absolute minimum required for us to fulfil our end of the deal.

I don’t regret my assessment of their rudeness, but I do regret my response.

It might have looked like I was being humble, but it stemmed from my ego – as if my silence and lack of contribution was my way of punishing them.

As they say in footy, I should have played the ball, not the man.

Instead of casting judgement on rudeness, I should have doubled my efforts in making better suggestions, or explaining my concerns over their bad ideas.

If I was right, surely I could prove it in a clear, logical way.

If I thought their plans would fail, it was my job to create better ones, even at the risk of being embarrassed again.

Not because I expect them to like my ideas, but because it would have forced me to make more suggestions, and speed up my development.

These ideas, despite likely being rejected, could have then been re-used for other, politer clients.

Ignoring the cashflow crisis

Most social entrepreneurs will tell you that they are looking for investment; that in 18 months they’d like to raise somewhere between $500k - $1m.

Having worked with several hundred of them, the more accurate goal is to be able to cover their payroll expenses in two weeks’ time.

I heard Wouter Kersten uses a great expression: CFIMITYM

Cash Flow Is More Important Than Your Mother.

For the groups I was assisting, this was certainly the case.

It’s one thing to talk about grand plans, social impact measurement and how they’re going to scale up the business.

The problem is, if there’s a cashflow issue, the entrepreneur is going to be pre-occupied and losing sleep.

My regret is that I didn’t get more involved in stopping the bleeding.

If I knew that these were the issues, and I claim to be a professional advisor, then I should have done more to help – even outside of work.

I wish I had dived into their numbers, tried to find quick cost savings, created plans for making new sales, or assisted with their customer acquisition/retention strategies.

I also wish I’d have educated myself earlier – to spot the cashflow issue and then not learn how to fix it was complacency.

I justified it as not being my job, but in reality it would have made my job much easier.

Letting doubt get in the way

Imposter syndrome is real – the constant anxiety that whispers in your ear;

“You’re about to be exposed as a fraud”.

This was certainly the case for me in my first two years of consulting.

I had one or two specialties and clung to them tightly.

Not because I was passionate about them, but because they felt safe – immune from criticism.

These nerves can be channelled into something good – it fuelled my reading and professional development.

It made me read 30-40 business books a year, and seek out advice wherever possible.

But the nerves also prevented me from helping people.

Experience and books can refine your “gut instinct”, but fear can still stop you from articulating your thoughts.

It’s why I never wanted to ask “What can I do to be useful for you?” – because I was afraid that whatever they requested would reveal my shortcomings.

The book that changed my mind was Getting Naked by Patrick Lencioni, about the power of vulnerability in consulting.

This is the willingness to be wrong, to ask potentially dumb questions, and to push your ego aside when trying to solve a problem.

It seems there’s two common themes that runs through my mistakes.

The first is that my regrets are all to do with omissions.

I don’t regret the things I did, but I regret what I didn’t do.

Secondly, when times were tough, my defence mechanism was to do what was required of me, and nothing more.

If the situation was making me miserable, I’d try and minimise my exposure to the problem.

In reality, had I pushed a bit harder, the work would have become easier.

I’m grateful to my employers and customers for sticking with me over the years and helping me develop, and for the lesson these mistakes have seared into my mind.